I started in September 2018 intending to build a small, narrative-driven RPG as a follow up to my last, very short and experimental game The Singularity Wish. The premise is simple, take the setting of the SCP Foundation, game mechanics from Final Fantasy Tactics and D&D 5e, and make an old-school, turn-based grid RPG (with classes!). My end goal was pretty ambitious: to recapture the feeling of old RPGs like Baldur’s Gate and Planescape: Torment. Since I’m a solodev, I would need to scale down features and content, but I wanted that sense of adventure, discovery and interesting characters. It wasn’t just nostalgia, it was a need to fill a void in where the industry is lacking. So I set out on making a RPG, with a combat system built from scratch, on a budget. The budget was whatever I can spare out of my own bank account (and later, some help from Kickstarter).

My list of tools were all fairly inexpensive:

Software

- Sublime text – coding, perhaps not the best tool for editing javascript but worked well enough for me

- Aseprite – pixel art creation and editing

- Gimp – a cheaper solution to Adobe cloud when it comes to image editing software, and after having worked with both, easier to learn too

- RPGMaker MV – to provide the basis of my game. A solid, if very limited gamemaker, but great if you’re building old-school 2D rpgs

- OBS – great recording software

- Movavi – perhaps not the most popular video editing software, but I like it and it’s relatively affordable

Hardware:

- Dell Inspiron 15 – a horrible laptop to build a game on, but it was what I had so I made do with it

- MacBook Pro – an upgrade in some respects to the Dell, and needed this to export the game to mac ios, as well as testing and all that other good stuff

Help:

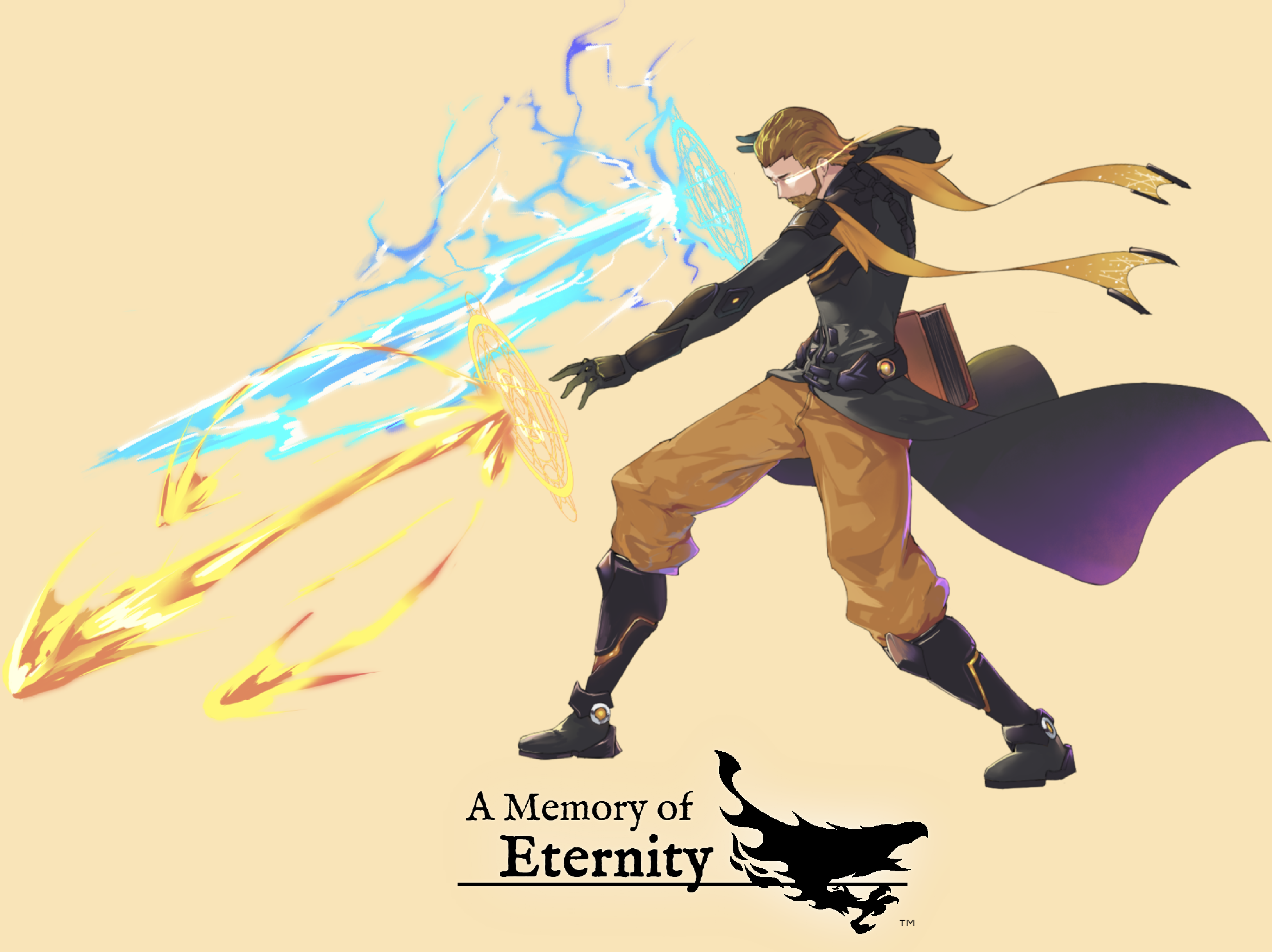

- A number of contracted artists who helped me greatly with promotional art, game assets, tiles, etc

- Professional musicians who helped me pick the music mix and composed the game’s theme

- Programmers who helped me muddle my way through code and attempting to twist RPGMaker into something it really wasn’t designed for

- The vast and wonderful community dedicated to making games, especially on RPGMaker and creating wonderful plugins

- My D&D groups who pitched in on ideas for building a turn-based combat system that’s both fun and fair

Obstacles:

- Scope-creep – many gamedevs have a habit of scope creep, as we all notice neat little ideas and features that can enhance our games during development, and inevitably we try to incorporate some of them. Perhaps it’s something you see in another game, or something a supporter said in Discord. As time goes on, these features have a habit of growing, and one of the most difficult things is deciding when a feature has no part in your game, especially if it’s already implemented, and implemented well. Sometimes you have to kill your darlings.

- Financials – If you tell people that you’re building a game on a $6,000 budget, some will probably laugh in your face. Inevitably there will be those who tell you that it can’t be done, listing off the average salary of a junior-level programmer in the midwest, the costs of artists, writers, voice actors, etc. However, low-budget games has always been the rule of thumb for hobbyists and solodevs. I’ve said before that gamers shouldn’t have the romantic notion of gamedevs as toymakers tinkering away in a workshop, but if that applies anywhere, it’s to these people. The games industry is a massive money maker fueled by scummy monetization practices and shady marketing practices, but hobbyists are just people working out of their bedroom or garage, building games because it’s what we want to do. Many of us try to be pro-consumer: no DLCs, no microtransactions. Pay for the game and it’s yours forever (Itch.io is pretty good regarding the no DRM thing since you get a zip of the game files). This, unsurprisingly, does not translate to money-making well. My low budget placed a hard ceiling on how polished my game would be, even after a successful Kickstarter that was 250% over the goal (but I only asked for a measly $800 to finish out some assets).

- Work-life balance – Like many hobbyists, I have a 40hr/week day job to pay the bills. Working an additional 30hrs gamedev on that is a hard sell, but I did because I liked it. Even now, I still really, really enjoy my time working on games. However, my body (and mental state) didn’t. A few months into the project I could feel the steady buildup of fatigue in the back of my mind. There were two inevitable consequences, and I’ve felt both before. Either I crashed and stopped development, or I would grind through and end up resenting gamedev. Those are the reasons why many talented gamemakers leave the business (well, that and the low pay and clueless upper management). I decided to pull back a bit, made sure I had enough time to relax, and more effectively plan out the upcoming stages of development.

- Gameplay – I’ll be the first to admit I’m not an experienced game designer. My strong suit has always been writing. It’s what I studied in college, it’s what my day job is, and most importantly, it’s what I really like. Part of the reason why I gravitated to gamedev was because of the lack of good stories outside walking simulators and experimental games. But gameplay? I had a lot to learn, and I’m still learning. I had spent most of my life playing various RPGs, so I have a good knowledge of what systems I liked, and what systems I didn’t. I wanted to build a game that was more than just about grinding, it required a good sense of short-term combat tactics and long term build strategy. What I came back to was D&D and all those memories of learning different builds, and all those dangerous little squares where taking the wrong action in any one turn could cost you your life – or someone else’s. I wanted to take the best part of D&D and put it in my game, perhaps even refine it a bit. I underestimated what an undertaking that would be.

- Narrative – I figured narrative was going to be the easy part, but I should know by now that it never is. I’m a writer by training and trade, and words come fairly easily to me (even if proofreading does not). A 10-hour game shouldn’t be that much of a problem, I said. The premise is already there, the lore is already there, everything is already in place. Well, everything except for the characters, who are the #1 most important thing in a party-based narrative RPG. Why should the player care about these people? For that matter, who even are these people? Lore is easy, settings are easy. Characters are hard. That is for the simple fact that no matter what kind of crazy fantasy world you’re making up, characters have to be relatable, and they have to act according to their own internal logic. That means that writing good characters requires a fair bit of time, and of consideration.

Phase one: Planning, gathering ideas, first steps

The first step was really deciding what set of tools to use. I wanted a robust, 2D top-down RPG that felt great to play, had solid combat gameplay and wasn’t horrible to look at. I didn’t feel as if I have the right amount of experience or budget to go forward with Unity or Unreal (without making horribly janky asset flips, at any rate) so I settled on RPGMaker, which I already had experience with. Now RPGMaker is a wonderful tool but it has garnered a reputation for producing low-effort, low-quality games, perhaps even more so than Unity. This is in part due to its extreme ease of use. Practically anybody can pick it up and make a game almost immediately (perhaps after watching a few videos). However, RPGMaker is very limited in what it can do: it’s designed for one thing and one thing only, Final Fantasy-style RPGs. Trying to coax it to do anything else requires a lot of plugins, tinkering, and messing with the code directly. What I ended up with was a massively modded Frankenstein version of the original software, with random bits sticking out.

During this time, I was out gathering ideas of what features to add to the game. Reddit was very helpful in shaping my progress, especially smaller subs like r/rpg_gamers and r/strategyrpgs. We are currently in something of a CRPG/SRPG revival, as many small indies (although most are still way bigger than me) are bringing new ideas and IPs into the fold. How am I going to make my game (which doesn’t look like anything special in terms of graphics) stand out among all these others? Well, if you don’t have (or can’t afford) style, try for substance. This means two things: gameplay and story, the two most important things to an RPG.

It was at this time that I re-evaluated the SCP-style setting of the game. If you haven’t discovered the SCP Foundation, it’s a wonderful rabbit hole of creepy scientific catalogs of unique and anomalous (fictional, hopefully) things. Statues that break your neck when you blink and lighthouses from another dimension. Taken as a whole, there is a very surreal, uneasy, lovecraftian horror to it. Was that what I wanted for my project? Yes, but perhaps not in the same way. In a Lovecraftian horror, the heroes ultimately succumb to an uncaring (yet still hostile) universe. That is not my story at all. My story was about the triumph of ordinary people (power-grinding office workers) in the face of unbelievable power. It’s really a story of defiance, against both omniscient AIs and unbelievably ancient primordial beings.

Phase two: Welcome to the (good) grind

If planning, development and release can be conceptualized as a sandwich, the first and last parts are undoubtedly lame white bread. Important yes, because they both provide a foundation and topper for your work, and critical yes, because otherwise your hands would get all dirty with sauce, but ultimately not where the meat of the work is. The meat is development. The actual process of building. Not sure what to say about the process of development other than the fact that it is incredibly tedious, exciting, frustrating and satisfying in equal measure. When it works, it’s both a job and a joy at the same time.

My usual routine was working 8 hours at the day job dreaming of my game, hurrying back home, scarfing down whatever was available in the fridge, and then sitting down to another 3-4 hours of work. Sometimes it was a slog, making sure triggers worked correctly, or testing animations, or playing the same battles over and over again to catch bugs. Other times it was probably the most fun anybody can have sitting in the semi-dark in their underwear. I would edit art, write and create things that never should have been, and it was great.

Phase three: Closed beta test, feedback, marketing

The time of the closed beta test came and I sent out keys to all my kickstarter backers who requested one, as well 100 extras which went first come first serve. I targeted specifically RPG enthusiasts, SCP fans, and SRPG players. Even a few old guard grognards (an affectionate? nickname for old school RPG players) snuck in. I had approached the beta with trepidation, but the feedback blew me away. Lot of people really enjoyed where the game was heading, and perhaps best of all, plenty of people provided useful, constructive feedback and where the game should go. Here’s a truth about gamedev, at least when it comes to devs who aren’t too full of themselves: we’ll never turn away useful feedback, and while there may not be time to implement it, it’s always appreciated.

The other thing is that for solodevs, a positive comment is about as precious as a sale. We want to be validated, to see that our ideas have merit. And while we’re pretty thick-skinned, and you have to be sometimes, a simple comment like “this is really fun” goes a long way.

What doesn’t go a long way is a $0 budget when it comes to marketing. With Facebook being pay-to-play and organic reach (both on the internet at large and on steam) pretty much dead, there was little to do. I’ve worked in or around marketing for about a decade now, and I can say that without money, there is no marketing. But there are still other things I can do to get the word out. Talk to a few super small-time YouTubers, bloggers, streamers. Write long rants here on reddit (this is most assuredly a marketing post). Pretend to be relatively nice and decent person (this actually works pretty well). All to get a few more eyes on my steam page.

In the end I spent about $4,000 on art, graphics, music and sounds. $1,500+ was spent on hardware and software, and >$1,000 spent on programming, business costs and other misc stuff. I ran super lean and wherever I could pitch in with my own work, I did.

Where am I at now?

I’ve just launched my game in early access on Steam. Full disclosure: early access is just really another name for an open beta, which is exactly where my game is at. Unlike other early access games however, I don’t intend to keep this in EA for years. I expect only a month of two before the game is in full release.

You can check it out:

Who should buy it?

- People who like RPGs, creepy stories, and lore not hand-fed to them

- People who like having a say in the ongoing development of games

- People who like hunting for bugs

- It’s about 50% cheaper now than at full release

Comments are closed