This devlog is more of a philosophical rant about large project gamedev. If you want a practical version, see my postmortem on my previous game here.

As of the time of writing, Memoirs of a Battle Brothel is complete and awaiting launch. It is a weird game. It is a confused mixture of genres, themes and storylines. It’s old-school, but also a modern, experimental fusion of JRPG and cRPG mechanics. It’s a serious, ponderous oaf masquerading as a sex game.

It took three years and change to complete. It won’t make me rich or famous. It’s barely more than a blip on Steam. I don’t even know if I would consider it a good game or not.

But I find myself still stubbornly proud of it. And part of that goes back to the old novelists’ wisdom of how writing inevitably takes something out of the writer. More than just your ideas and characters, and perhaps a fondness for buxom redheads (or whatever). It also takes something intangible. Perhaps a bit of your life force, or soul, or ka.

Creations are like children, and children should be loved by those who made them.

Vague lessons learned

You can only promise effort, not quality

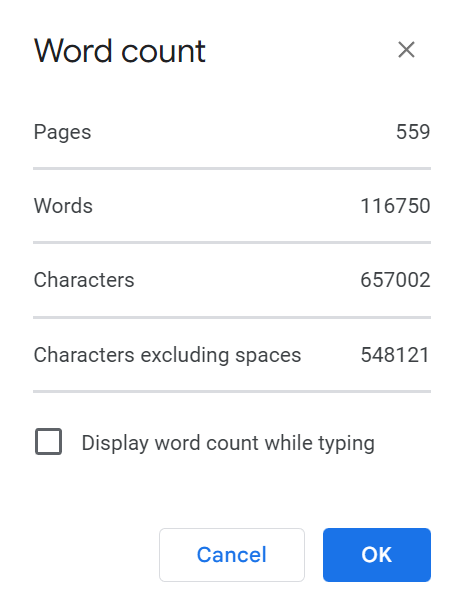

Compiled all my separate project docs and took a word count.

Anybody who has spent any time in gamedev will know you cannot make promises for quality. No matter your background, or who’s on your team, or how much money you have in your budget, or how many Twitch streamers rave about you.

Life throws curveballs at you. Things happen, and nothing should be taken for granted. The only thing that people can promise is putting in the effort, and even then, it’s not always delivered.

When I was younger and still in my novelist phase, I thought I was a bit of a hot shot. My prose was killer, I had a great head of hair (I mean, I still do, but I did back then too), and the world was my big-tittied oyster. I approached solodev because it was a challenge, and I never shied away from putting in the work.

But then I ran into what I’ll call the Complexity Issue. At some point on bigger projects, even the most organized solodevs will run into a simple problem: they have too much to do, and they’ll get bogged down in choice overload. This can be exacerbated by many different things, including player feedback or scope creep.

The end result is that your original, singular vision for the project splits into different fragments. You start adding features that are interesting, but not entirely needed. Maybe you go through an art change or two. Even your writing is affected, and the narrative loses cohesion.

All of these are prime reasons why games fail. Big studios experience it, and so do solodevs. However, solodevs do not always have the mental bandwidth to notice when a failure occurred. When you have a team of writers and editors on dialogue, they should notice something right away. A solodev does not, because they simply won’t have time for it.

This creates a kind of fuzzy spiderweb when I near the end of a big project. If something can be more than the sum of its parts, it can also be less.

I honestly don’t know if I’ve fallen victim to one of the many things that ruin games, and it’s nearly impossible to measure when you’re so close to a thing’s creation.

Try as I might, I can’t guarantee something is good. But the next best thing is promising effort. It’s not foolproof, but more often than not, it will deliver the outcome you want. And it’s the only real solution I’ve found to the Complexity Issue.

The bigger something is, the harder it is to end it

I think we’ve all marveled at creators who’ve slaved away for 7+ years on the same project. Whether or not the project ever releases, or is actually well-received or not, you have to give them credit for (usually) the tremendous amount of work they put in. After all, they’ve invested a significant portion of their lives in their art, and that’s a heavy price to pay.

A lot of them never finish, even when so close to the finish line, and I got to find out first-hand why.

It’s hard to finish something you spent so much time on.

There’s lots of practical reasons, such as meeting fan expectations, checking off things you promised during crowdfunding, etc. But most of it is just… endings matter. And how you end something that you’ve invested in so much, matters a lot.

You want more time, especially if you have certain perfectionist tendencies like I do. Time to make things right, to finish things the way you’d like. And… if no one is holding your feet to the fire, you’d want that time to last as long as possible.

But perfect is the enemy of any commercial enterprise, and we have to make do with good enough. The funny thing, almost bordering on irony, is that a lot of the time that “good enough” is great. Creators really are in dire need of an editor sometimes.

Even vaguer conclusions

And now, like all gamedevs big or small, I am engaged in that wonderful ritual of anxiety as launch looms. Soon, I will be glued to the Steam sales report page and be calculating which of my bills I will be able to pay. But financial worries aside, it’s a wonderful time. Other than simply watching numbers go up, the thing I crave is feedback. To see a community come to life just a little bit, and new players discover a game they may really like. And of course, to catch bug reports.

There is something primal about watching others experience something you’ve created. Something that stretches back to when one cave dweller showed another their rendition of a woolly (is that really how you spell it?) mammoth. Perhaps that’s why some gamedevs are drawn to an industry where success is rare and abuse is rife. Perhaps it’s why it motivated me to climb a very steep mountain.

Personally, I agree that mountains are there to be climbed, if only so we can marvel at the view at the summit.

Lastly, I’d like to thank my small but wonderfully supportive community of fans and backers, as well as all the people who helped contribute to the project. Solodev is usually never completely alone, and that’s probably the best way to make a game “on your own.”

Comments are closed